Linked Lists Compared

A short overview of linked lists implemented in functional, procedural, and an object-oriented way

Linked Lists Functional, Procedural, and Object Oriented; Part 1

Over the last 2 weeks, I’ve been building a singly linked list implementation from scratch in Haskell, Ruby, and C. I originally did it just to become a little bit more sharp in these languages, but what I found was really interesting, so I thought I would share my findings in a blog post.

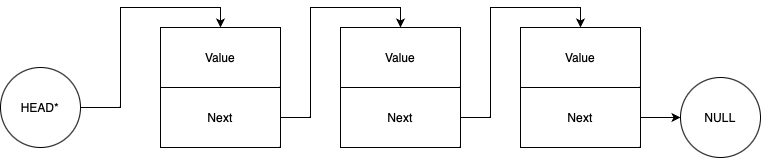

What is a Linked List?

A linked list is one of the most foundational data structures in computer science. In fact, they come as a base language feature in many languages such as Ruby, python, and Haskell. They work by allocating memory for the data (in my implementations this is an integer), as well as a pointer to the next node in the list. Of course, you can embellish them further to turn them into doubly linked lists, circular lists, arraylists, etc. but for the sake of simplicity, I’ve just implemented vanilla singly-linked lists.

In terms of theoretical time efficiency, it has the following properties on its basic operations:

| Operation | Efficiency |

|---|---|

insertHead(data) |

O(1) |

insertTail(data) |

O(n) |

deleteNode(Node) |

O(n) |

printList() |

O(n) |

size() |

O(n) or O(1) - implementation dependant |

In practice, it will usually be much more efficient, both in memory and time, to use an array, because you will get a massive speed boost from your CPU’s cache, and save memory because you don’t need to store an extra pointer for each node. However, many developers, if not most developers, don’t need to worry about efficiency because we don’t work with systems that will see enough load for this to make a meaningful difference.

I plan on measuring the performance of all of these implementations later on this year to demonstrate this.

The C Implementation

The C implementation can be found in my programming tools repo here I’ll keep that version updated if I find any issues in my implementation, but here’s a copy of it so that you don’t need to open too many tabs to read this blog post.

Don’t bother reading all of the code in depth, just take a glance and move on, we’ll do our analysis once we’ve seen all of the implementations.

linked-list.h:

typedef struct Node {

struct Node* next;

int value;

} Node;

typedef struct List {

Node* head;

} List;

char* print_list(List* list);

List* tail_insert(List* list, int val);

List* head_insert(List* list, int val);

List* remove_node(List* list, Node* node);

int free_list(List* list);

int size(List* list);

linked-list.c:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include "linked-list.h"

#define INIT_PRINT_BUFFER_SIZE 255

#define MAX_STR_SIZE_FOR_INT 10

#define SIZE_OF_ARROW_STR 4

char* int_to_string(int n) {

int size_of_string_representation = snprintf(NULL, 0, "%d", n);

size_of_string_representation++; // add 1 for terminating '\0' character

char* buffer = malloc(sizeof(size_of_string_representation));

snprintf(buffer, size_of_string_representation, "%d", n);

return buffer;

}

char* print_list(List* list) {

int buffer_size = INIT_PRINT_BUFFER_SIZE;

char* print_buffer = malloc(buffer_size);

Node* curr = list -> head;

int i = 0;

while (curr != NULL) {

char* curr_val_str = int_to_string(curr -> value);

int curr_val_str_len = strlen(curr_val_str);

// double buffer size if we're running out

while (i + curr_val_str_len + MAX_STR_SIZE_FOR_INT + SIZE_OF_ARROW_STR > buffer_size){

buffer_size = buffer_size * 2;

print_buffer = realloc(print_buffer, buffer_size);

}

// Copy current value into print_buffer

for(int j = 0; j < curr_val_str_len; j++) {

print_buffer[i++] = curr_val_str[j];

}

free(curr_val_str);

print_buffer[i++] = ' ';

print_buffer[i++] = '-';

print_buffer[i++] = '>';

print_buffer[i++] = ' ';

curr = curr -> next;

}

print_buffer[i] = '\0';

return print_buffer;

}

List* tail_insert(List* list, int val) {

Node* head = list -> head;

if(head == NULL) {

Node* item = malloc(sizeof(Node));

if (item == NULL) {

printf("Malloc failed");

return NULL;

}

item -> next = NULL;

item -> value = val;

list -> head = item;

return list;

}

Node* curr = head;

while (curr -> next != NULL) {

curr = curr -> next;

}

Node* item = malloc(sizeof(Node));

if (item == NULL) {

printf("Malloc failed");

return list;

}

item -> next = NULL;

item -> value = val;

curr -> next = item;

return list;

}

List* head_insert(List* list, int val) {

Node* new = malloc(sizeof(Node));

if (new == NULL) {

printf("Malloc failed");

return list;

}

new -> value = val;

new -> next = list -> head;

list -> head = new;

return list;

}

List* remove_node(List* list, Node* node) {

if (list == NULL) {

printf("cannot remove item from a null list");

return list;

}

Node* curr = list -> head;

if(curr == node) {

list -> head = curr ->next;

free (node);

return list;

}

while (curr -> next != node) {

if (curr == NULL) {

printf("node not found in list");

return list;

}

curr = curr -> next;

}

Node* n = curr -> next;

curr -> next = curr -> next -> next;

free(n);

return list;

}

int free_list(List* list) {

Node* curr = list -> head;

while(curr != NULL) {

Node* next = curr -> next;

free(curr);

curr = next;

}

free(list);

return 0;

}

int size(List* list) {

Node* curr = list -> head;

int list_size = 0;

while (curr != NULL) {

list_size++;

curr = curr -> next;

}

return list_size;

}

Again, don’t bother reading it all now, just take a look and move on.

The Ruby Implementation

The Ruby implementation can be found in my programming tools repo here

Again, don’t bother reading it all in depth, just take a look at it, see the forest, not the trees, and move on.

node.rb:

class Node

@val

@next

def initialize(value:, next_node:)

@val = value

@next = next_node

end

def val

@val

end

def next

@next

end

def set_val(value)

@val = value

end

def set_next(next_node)

@next = next_node

end

end

linked_list.rb:

require_relative "node"

class LinkedList

@size

@head

def initialize()

@size = 0

@head = nil

end

def insert_head(val)

new_head = Node.new(value: val, next_node: @head)

@head = new_head

@size += 1

self

end

def insert_tail(val)

if @head == nil

@head = Node.new(value: val, next_node: nil)

@size += 1

return

end

current = @head

while current.next != nil

current = current.next

end

current.set_next Node.new(value: val, next_node: nil)

@size += 1

end

def delete_node(node)

if @head == node

@head = node.next

@size -= 1

return

end

current = @head

while current.next != node

current = current.next

end

if current.next != node

puts "not found"

return

end

current.set_next current.next.next

@size -= 1

return

end

def size()

@size

end

def to_string()

current = @head

list_str = ""

while current != nil do

list_str += "Node: #{current.val} -> "

current = current.next

end

list_str

end

def head()

@head

end

end

The Haskell Implementation

The Haskell implementation can be found in my programming tools repo here

Again, don’t worry about understanding it all in depth right now, just take a look and move on. I’ll explain things in more detail in the analysis section.

module LinkedList where

data Node = Node

{ val :: Int

, next :: Node

} | EmptyNode deriving (Show, Eq)

tailInsert :: Node -> Int -> Node

tailInsert EmptyNode value = Node value EmptyNode

tailInsert head value = Node (val head) (tailInsert (next head) value)

headInsert :: Node -> Int -> Node

headInsert head value = Node value head

printList :: Node -> String

printList EmptyNode = ""

printList node = show (val node) ++ " -> " ++ printList (next node)

removeNode :: Node -> Node -> Node

removeNode EmptyNode _ = EmptyNode

removeNode head nodeToRemove = let

headIsValue = nodeToRemove == head

in

if headIsValue then

removeNode (next head) nodeToRemove

else

Node (val head) $ removeNode (next head) nodeToRemove

size :: Node -> Int

size EmptyNode = 0

size node = 1 + size (next node)

Analysis

Analysis Caveats

First, I want to talk a little bit about my skills in each language.

C

I wrote some fairly small but complicated projects in C in university, but have had no professional experience with the language. I’ve also never had a proper code review in the language, leaving me very ignorant to best practices and industry standards.

I find

beauty and utility in C’s simplicity, but that doesn’t mean that I have a firm

grasp on the best way to do anything in the language. This is a naive approach.

I’m aware that there is a better way to do remove thanks to Linus Torvalds,

but didn’t implement it to make this more beginner friendly.

I’m sure there are many more improvements that I don’t know about. In fact, I would wager that if you got 100 skilled C developers to make the same project every single one would be better than my implementation in nearly every way.

Ruby

I currently help maintain a fairly large Ruby on Rails project at Leanpub. I’ve been in this role for about 7 months now, so I have a solid grasp on the fundamentals of the language, but there are still some things that trip me up in the language.

Just like in C, I’m sure that there are improvements to be made here and that my style might not match what is standard for Ruby programmers, but all in all I’m more confident in this implementation than I am the C implementation.

I think that if you got 100 skilled Ruby developers to make the same project, many would look like mine, though I suspect that many wouldn’t split up the implementation into a Node class and a LinkedList class. That’s the Java programmer in me coming out.

Haskell

I currently help maintain the book generation workflow at Leanpub, which uses Haskell as its main language. I have written production Haskell, which automatically makes me cooler than 99% of other developers out there.

That being said, I only have a few months of professional Haskell experience, and there is still a lot to know about the language.

All that being said, because there is so little to the Haskell implementation, I would bet that all 100 skilled Haskell developers would make an implementation very much like mine, if given the challenge.

Development Time

With the disclaimer out of the way, let’s talk about the most visible cost to an engineer thinking about using any of these languages: development time.

I didn’t keep track of my development time in any of these languages, simply because I didn’t think it would make a fair comparison between them, because I am not equally efficient in these languages. However, we don’t need to know exact billable hours to determine a winner here. Haskell took me the least amount of time to implement, followed by Ruby, followed by C.

I think this should be visible why this is in the following table:

| Language | Total lines of code (all implementation files) |

|---|---|

| Haskell | 35 |

| Ruby | 97 |

| C | 147 |

Why is that? It’s the same data structure, implemented by the same developer.

Let’s take a look at each print_list implementation to see why first.

For all of the implementations, it returns a string representation of the list formatted as such:

34 -> 42 -> -42 ->

Let’s start with the C implementation:

C

#define INIT_PRINT_BUFFER_SIZE 255

#define MAX_STR_SIZE_FOR_INT 10

#define SIZE_OF_ARROW_STR 4

char* int_to_string(int n) {

int size_of_string_representation = snprintf(NULL, 0, "%d", n);

size_of_string_representation++; // add 1 for terminating '\0' character

char* buffer = malloc(sizeof(size_of_string_representation));

snprintf(buffer, size_of_string_representation, "%d", n);

return buffer;

}

char* print_list(List* list) {

int buffer_size = INIT_PRINT_BUFFER_SIZE;

char* print_buffer = malloc(buffer_size);

Node* curr = list -> head;

int i = 0;

while (curr != NULL) {

char* curr_val_str = int_to_string(curr -> value);

int curr_val_str_len = strlen(curr_val_str);

// double buffer size if we're running out

while (i + curr_val_str_len + MAX_STR_SIZE_FOR_INT + SIZE_OF_ARROW_STR > buffer_size){

buffer_size = buffer_size * 2;

print_buffer = realloc(print_buffer, buffer_size);

}

// Copy current value into print_buffer

for(int j = 0; j < curr_val_str_len; j++) {

print_buffer[i++] = curr_val_str[j];

}

free(curr_val_str);

print_buffer[i++] = ' ';

print_buffer[i++] = '-';

print_buffer[i++] = '>';

print_buffer[i++] = ' ';

curr = curr -> next;

}

print_buffer[i] = '\0';

return print_buffer;

}

That’s 36 lines of code just to print the list. That’s one more line of code than the entire Haskell linked list implementation.

Why it’s so long is clearly visible immediately: memory management. Neither Haskell nor Ruby has to double the size of the string buffer if it gets too large, neither one had to remember to add the null terminator.

I’m aware that there are ways to make my implementation smaller, but the point still stands: Manual Memory Management comes with a development overhead

If you’ve never seen C code before or worked manually with memory, you would have a very hard time understanding what’s going on here. It might take you a long time to understand that I’m iterating through my linked list and iterating through arrays of characters (the canonical C string implementation) to concatenate together the final returned value.

C’s traditional function naming style doesn’t help here either. Why does

snprintf get called twice in the int_to_string method in two seemingly

unrelated ways?

Overall, while it is almost certainly more efficient than anything else on this list, the C implementation took the most time and uses a lot of concepts that a new developer would need to understand somewhat deeply to work on, such as the difference between the stack and the heap, memory management, strings in C, etc.

What about the Ruby implementation?

Ruby

def to_string()

current = @head

list_str = ""

while current != nil do

list_str += "Node: #{current.val} -> "

current = current.next

end

list_str

end

That’s much more concise. Since Ruby has a really nice string class and string interpolation to build on top of, it’s much more concise than the C version.

However, even though it’s more concise, it’s still legible to a programmer that has never seen Ruby code before.

As well, it has abstracted away many of the complexities of the C program.

The final step in this journey is the Haskell implementation.

Haskell

printList :: Node -> String

printList EmptyNode = ""

printList node = show (val node) ++ " -> " ++ printList (next node)

Wow, that is concise, bordering on terse. If you’ve never seen Haskell before, you may not understand what is going on here. And, on top of that, it’s recursive, a concept that people usually take longer to grasp than loops.

Note, that in both the C and Ruby implementations, I could have implemented the functions recursively, but people would have looked at me funny. Fact is, outside of pure functional languages that don’t have loops, recursion isn’t used as often as loops in industry, even if they would make more concise code.

I’m not sure if it’s because Haskell has such a different syntax, or if it’s because it has such a different style, or if it’s because it is actually just difficult to understand by nature, but I find that people are very likely to have a difficult time looking at a piece of Haskell code and understand what’s actually going on in the program, far more than something like Ruby or Java.

My Personal Opinion

All three of these linked list implementations are in languages that I enjoy for different reasons. Haskell and C, in my eyes, take the same simplicity principle to the extreme in different ways. C takes simplicity of the low-level to an extreme, and Haskell takes simplicity of the high level to an extreme. I like simplicity in my code, which is why I love both of these languages. Ruby, on the other hand, splits the difference nicely.

If I’m doing work on systems where footprint, performance, and memory usage are important considerations, I’m going to choose C every time (especially if security isn’t that important, such as for devices that are never connected to the internet). Neither Haskell or Ruby is going to give me as much control over performance. However, if I’m just trying to build a system where performance isn’t as much of a concern as development time, I would probably want Ruby, Haskell, or another such high-level language.

If we were to look at development time for this one data structure as our only data point, we would want to choose Haskell. However, there are many other dimensions to analyze here (see appendix A for more), and I would caution against using this single data point as evidence for Haskell’s superiority.

Conclusions

I’ve taken the time to implement the most basic data structure in C, Haskell, and Ruby, and compared the development time and development experience between the 3 languages. There is a lot more dimensions to analyze than this, and I plan to in later blog posts. However, I think the results from this first bit of analysis are interesting. The Haskell implementation took the least amount of time, followed by Ruby, followed by C. C took so long because it takes a while to deal with memory management and strings as arrays, and Haskell took so short because it made heavy use of the inherent recursive nature of the data structure, something that Haskell handles very well.

Appendix A: Futurie Analysis

If you’re interested to see these implementations compared on the following dimensions, please follow me on LinkedIn where I post all of my blog posts.

- Memory usage

- CPU usage

- Footprint (compiled size)

- Maintenance/Extensibility

- Safety/Security

- Tooling

- Paradigm

I plan on analyzing all of these dimensions soon. I’m excited to see if the Haskell implementation uses as much memory as I think it will.

Appendix B: Further Improvements

I plan on redoing these implementations later next year, tracking my time as I do. I want hard numbers for exactly how long things take. I think that even though I don’t know all the languages equally well, there might be large trends in that data worth discussing.